Comet C/2025 R2 SWAN : journey of a visitor from the Oort Cloud

Comet C/2025 R2 SWAN: a visitor from the Oort Cloud

\n\nCaptivating Introduction

\nAs we look up at the night sky, we can almost hear ancient stories that speak of comets as travelers lost in the cosmic void. In 2025, a new visitor drew the attention of enthusiasts: the comet C/2025 R2 SWAN. Discovered thanks to the SWAN sensor on the SOHO satellite, it reminds us that the Solar System is a theater where tiny objects can trigger spectacular phenomena when they approach the Sun. With its greenish tail and slow motion in the sky, SWAN invites everyone to wonder what a comet really is and why these travelers remain a source of wonder as well as learning.

\nWhat is a comet?

\nA comet is essentially a small icy body roaming through space. When it approaches the Sun, the heat melts its ices and releases gases and dust. This activity creates a bright coma around the nucleus and, often, one or more tails that can extend across degrees of the sky. The nucleus of comets is typically a few kilometers to a few tens of kilometers in size, but what strikes observers most is the instantaneous nature of the light and the shapes: the ellipticity of the orbit, the color of the gases, and the dance of the dust in the solar wind.\n

\nComets originate from two mythical regions of the Solar System: the Oort Cloud, a distant spherical halo that harbors billions of icy debris, and the Kuiper Belt, closer to the Sun, where smaller and more chaotic objects lurk. When they depart from these edges, they become ephemeral visitors to the celestial plane, visible from Earth for a few weeks to a few months, depending on their activity and orbit.\n

\nDiscovery and nature of SWAN

\nSWAN is a sensor capable of detecting the ultraviolet imprint of hydrogen released when water molecules dissociate around the comet. In the case of C/2025 R2 SWAN, observations revealed a tail reaching between two and two and a half degrees, and a greenish coma typical of cyanogen gas and diatomic carbon present in cometary gases. This green coloration is a purposeful visual signature of the gaseous composition. The comet was officially designated and tracked as one of the discoveries associated with the SWAN instrument, demonstrating the usefulness of space sensors in the study of distant comets.\n

\nOrbital parameters and origin

\nInitial orbital clues for SWAN came from short sets of observations. The initial hypothesis suggested a comet with a very long period, possibly originating from the Oort Cloud, with a perihelion near the Sun and a return expected in tens of millennia. Additional observations, notably data from STEREO A and the network of amateur astronomers, allowed estimating a much longer orbit but more accessible on human timescales: a perihelion around 0.5 AU (about 75 million kilometers from the Sun) and an aphelion distance around 150 AU, with an orbital period of a few centuries. This revision nicely illustrates the importance of ongoing measurements and integrating additional data to refine our dynamic models.\n

\nPerihelion passage and near-Earth approach

\nThe perihelion is the point at which the comet is nearest the Sun. For SWAN, this moment occurred around September 2025, when the comet was near the Sun and invisible from Earth at that stage due to the angle and illumination. The approach to Earth, expected around October 20, 2025, placed the object at about 0.26 AU from us, i.e., about 39 million kilometers. This distance makes observation accessible with binoculars under favorable sky conditions and, for observers willing to use more modest means, potentially visible to the naked eye in places free of light pollution, depending on the exact brightness evolution.\n

\nEvolution of brightness and activity

\nComets can be surprising: C/2025 R2 SWAN experienced fluctuations in brightness in the second half of September, with a magnitude around 5.9, and observers noting an impressive tail and a greenish coma. Subsequently, estimates varied around a magnitude between 4 and 6 around October 20, though some forecasts remain cautious and suggest that the object might appear around magnitude 6, which reduces naked-eye visibility. As with many comets, the evolution strongly depends on the activity of the nucleus and the solar wind conditions.\n

\nCelestial path and stellar encounters

\nAfter its discovery, the comet traversed several regions of the sky. It moved from the constellations of Virgo and Libra toward Scorpius, then Ophiuchus and then Serpens and Scutum. This journey offered observers a spectacle: passes near notable stars such as Spica or Zubenelgenubi, then encounters near the nebulae M16 and M17. At the time it was approaching Earth, it was low on the southwestern horizon for observers in the southern hemisphere and rose higher each night for latitudes further north.\n

\nObserving tips for amateurs

\nObserved in a dark, moonless sky, the display can be subtle but rewarding. Here are some practical guidelines:

\n- \n

- \n When to observe: visibility depends on your latitude and local conditions; aim for the hours after sunset, when the comet is high enough and sky glow is low.\n \n

- \n Where to look: start toward the southwest then move toward the west after October 20, depending on the planned celestial path.\n \n

- \n What equipment: 10x50 binoculars are sufficient to spot the comet around magnitude 6; a small telescope can reveal the coma and tail details. A star map or a planetarium app can help locate the object in real time.\n \n

- \n Favorable conditions: dark skies, clear conditions and an unobstructed horizon are essential; stay away from urban areas to minimize light pollution.\n \n

Myths and realities

\nComets have long been surrounded by stories and often grandiose expectations. Some rumors can spread quickly, such as the idea of a meteor shower associated with a dust trail or a gigantic object hidden behind the Sun. Science shows that this is not the case: debris do not cross Earth’s orbit in the quantities expected, and any potential meteor shower is unlikely. Moreover, the idea that a comet is a single symbol with a telegraphed destiny dissipates in the face of the complexity of their orbits and activity, which depend on composition, nucleus size, and the influence of the solar wind.\n

\nThe green color of the coma comes from gas ionized by the Sun — cyanogen and diatomic carbon — which emit characteristic wavelengths when excited by solar UV. This palette reminds us that comets are not monochrome objects, but breaths of gas and dust that respond differently with each close approach to the Sun.\n

\nConclusion

\nThe comet C/2025 R2 SWAN reminds us that the Oort Cloud is a reservoir of rare and fascinating visitors. Its appearance, colors and journey offer both spectacle and a learning opportunity: understanding the origin of comets, how to observe them, and why their brightness can vary from one pass to another. For the curious, every observation is an open door to other cosmic phenomena, from icy objects in the outer reaches of the solar system to the living paintings drawn by the planets and stars in the night sky. Keep looking up and exploring star maps: behind every star lies a story waiting for you to tell.

\n

All

All

Dobson

Dobson

Refractors

Refractors

Ed & Apochromates

Ed & Apochromates

Newtonian reflector

Newtonian reflector

Schmidt Cassegrain

Schmidt Cassegrain

Maksutov-Cassegrain

Maksutov-Cassegrain

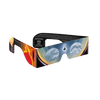

Solar

Solar

Researcher

Researcher

Focal reducer

Focal reducer

Intelligent

Intelligent

All

All

Equatorial

Equatorial

Alt/Az

Alt/Az

Harmonic

Harmonic

Tripods

Tripods

Accessories

Accessories

All

All

Wide angle

Wide angle

Zoom eyepieces

Zoom eyepieces

Reticulated eyepieces

Reticulated eyepieces

Barlow

Barlow

Plössl

Plössl

Binoculars

Binoculars

Atmospheric Corrector

Atmospheric Corrector

All

All

Visual

Visual

Photo

Photo

Polarisants

Polarisants

Solar Filters

Solar Filters

Accessories

Accessories

All

All

Color Cameras

Color Cameras

Monochrome Cameras

Monochrome Cameras

Planetary/Guiding

Planetary/Guiding

Objectives

Objectives

All

All

Binoculars

Binoculars

Spotting Scope and Monocular

Spotting Scope and Monocular

Elbows

Elbows

Optical Divider

Optical Divider

Mirrors

Mirrors

All

All

Bags and protections

Bags and protections

Supports and counterweights,

Supports and counterweights,

Camera adapters

Camera adapters

Focuser

Focuser

Collimation

Collimation

Heating band

Heating band

Cables

Cables

Collars

Collars

Computers

Computers

Fans

Fans

Others

Others

All

All

Weather Station

Weather Station

Thermometer

Thermometer

All

All

Observatory/Domes

Observatory/Domes

Accessories

Accessories

Askar

Askar

Baader

Baader

Bresser

Bresser

Celestron

Celestron

Explore Scientific

Explore Scientific

GSO

GSO

Optolong

Optolong

Touptek

Touptek

Vixen

Vixen

ZWO

ZWO